The first time I met Jorge in Roatán, I was just looking for a driver. I didn’t realize I had just met a local guide who would completely change how I understood the island.

I was standing at a bar in Roatán when I asked the bartender if he knew someone reliable to get around the island. Without hesitation he pointed across the room, “Talk to Jorge.”

Within minutes, the interaction stopped feeling transactional. He spoke about the island the way someone does when it isn’t just where they work, but where their life lives, where his adult daughter now has a child of her own, where he’s raising his young son, and where nearly every corner holds a memory tied to family, work, or survival. By the end of the ride, it felt less like arranging transportation and more like being briefly folded into someone’s everyday world.

Years later, I returned to the island and called him again. This time he drove a friend and I to the ferry for our onward trip to Utila. And then again, on my way back, he picked me up to take me to the airport while I was in rough shape after one… or five… farewell drinks the night before. We laughed the entire ride like old friends who had skipped months instead of years.

Some people quietly become part of how you remember a place. Jorge became part of Roatán for me.

So I asked him to tell me his story.

A Life Shaped by Water

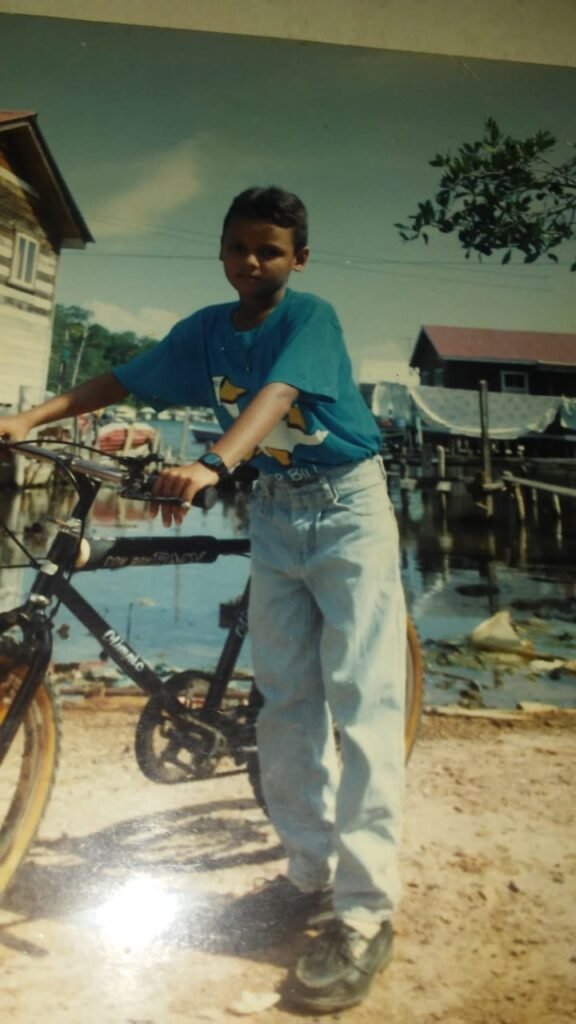

Jorge didn’t come to Roatán by choice, not at first. He arrived when he was five and wanted to go back to his grandparents. What stayed with him instead wasn’t a landmark or a beach, but a crossing, sitting low in a dugout canoe, tasting saltwater for the first time after growing up around freshwater, realizing without words that life had changed. He grew up in Port Royal, where pirates once landed, and later moved so he could attend school, something he believes quietly redirected the course of his life. By thirteen, the island had already asked more of him than childhood usually does. He went to sea to help his family. The first weeks were spent seasick, unable to eat, living mostly on water. Eventually the body learns what it has to learn. By seventeen he was second captain on a shrimp boat, and later he worked lobster boats that kept him away from home for months at a time, hundreds of miles offshore. He never talks about this dramatically. Just factually. Like weather.

“I didn’t have the childhood many children have,” he told me once. “But I’m proud of who I became because of it.”

And maybe that’s why he moves through the island the way he does now. Patient. Unhurried. Paying attention to people more than schedules.

A Home That Wasn’t About the House

When Jorge talks about where he grew up, he doesn’t describe the house itself so much as what lived inside it. It was small, simple, and held together more by effort than comfort, a mother doing everything she could and the quiet understanding that respect and honesty mattered more than what you owned.

“Many people live in large houses but without a home,” he told me once. “That house taught me humility, honesty, and love.” Part of why he went to sea so young was to help her, and even now one of his biggest goals isn’t tied to business at all. He wants to rebuild that same house so she can live there peacefully.

Somewhere in hearing that, his way of working makes more sense. He doesn’t move people around the island the way a driver points out stops, he moves through it like someone letting you step, briefly, into where he was raised.

The Day His Work Changed

Years later, after leaving life at sea, Jorge started driving taxis while slowly saving to buy a car of his own. It was meant to be temporary, just a step toward something steadier. One day he agreed to guide a couple around the island even though, after expenses, he would earn almost nothing. He spent the whole day with them. East side to west side. Morning into evening, not rushing, just sharing what he knew.

At the end they asked why he didn’t work for himself. He told them he was saving, but still about $3,000 short for his own car. A week later they called him. They had sent the rest.

“That’s when I understood my job wasn’t just driving,” he said. “It was how you treat people. Foreigners or locals, we’re the same.”

Since then, visitors have turned into returning faces, and returning faces into friends. He once told me about a bus stopping so more than thirty people could step off just to hug him goodbye. Moments like that don’t come from marketing.They come from being remembered.

The Island Visitors Don’t Always See

When I asked Jorge what he wishes visitors understood about the people who live here, he paused for a moment before answering.

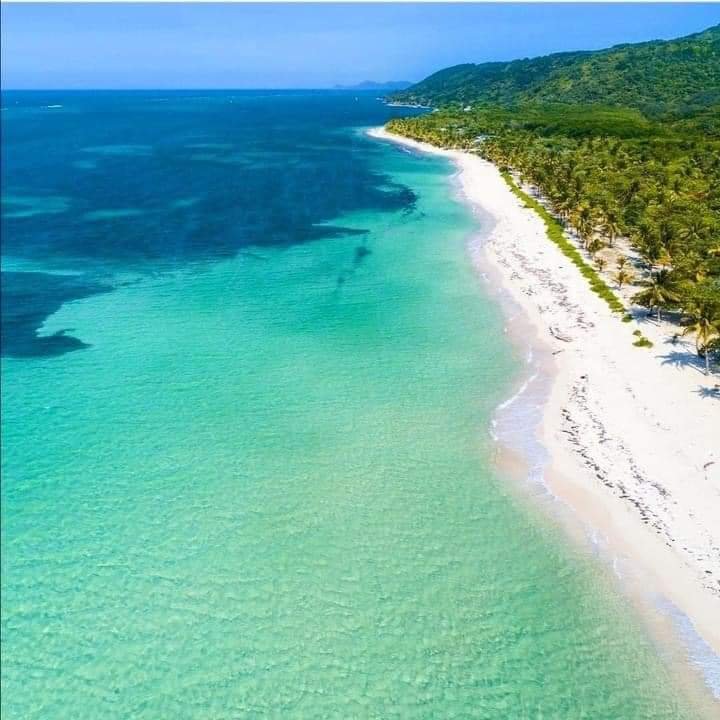

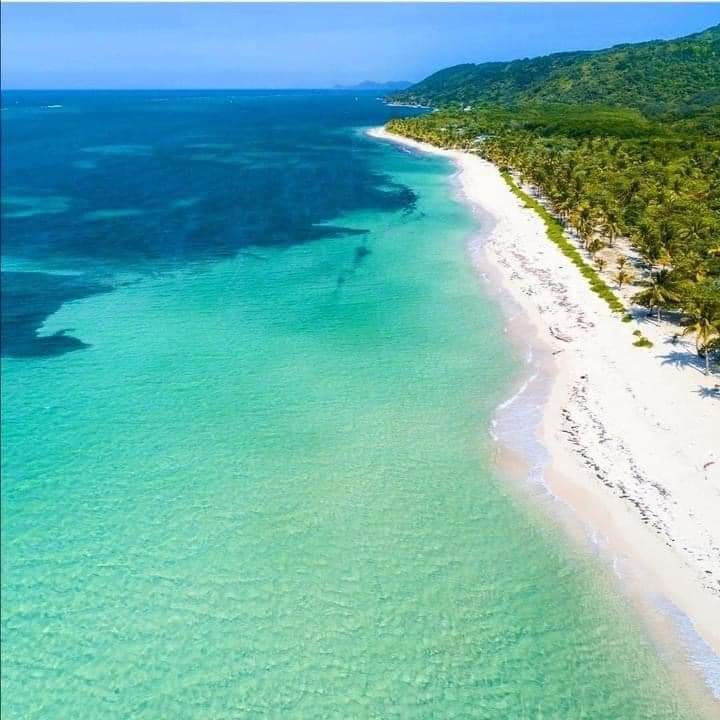

For most travelers, Roatán is a pause from real life, a week of sun and water and ease. And he doesn’t disagree that it’s beautiful. But for the people who call it home, the island asks for constant work. Even then, many never earn enough to travel and see their own country. Land that feels affordable to someone visiting can represent close to a decade of labor for someone living there. Behind the view, he explained, are families building a future one day at a time.

If he could explain his life through a place instead of a story, he would take you first to Oak Ridge on the east side of the island. When he was young, boats worked like school buses there, carrying children across the water each morning and back again in the afternoon. It’s where he spent part of his childhood, not an easy one, but a meaningful one.

He told me that when you visit that side of Roatán, you feel something different. People greet you the same no matter where you’re from. No hierarchy, no distance, just community.

To him, that part of the island is its truest form: the heart, the struggle, and the kindness that holds it together. That’s the real Roatán.

Loving a Place Means Protecting It

When I asked Jorge what he hopes for the future of the island, his answer wasn’t about growth or popularity. It was about care. He wants Roatán to welcome visitors, but not at the cost of what makes it home.

“When people ask me what I wish for the island,” he told me, “I want us to be better people to tourists, and that as we build, we also plant more trees so Roatán becomes greener and more welcoming.”

To him, progress isn’t the problem. Forgetting is. Cleared land sends soil into the ocean, covering the reefs that feed the fish. The same water that draws people here depends on small decisions made every day, by locals and visitors alike.

Responsible travel doesn’t have to be complicated. It can be choosing people over convenience, supporting locals instead of bypassing them, respecting the environment that hosts you, and remembering that you’re stepping into someone else’s home, not just their scenery. Places survive tourism best when visitors treat them like they matter long after the trip ends.

The Kind of Future He Wants

His dream isn’t extravagant. A house rebuilt for his mother. Education for his children. A boat so he can fish during slow seasons and provide for his family.

“I am proud to share my home with the world.”

Why This Story Matters

Travel isn’t just about where you go. It’s about who quietly holds the place together while you’re passing through. Meeting people like Jorge changes how you move through the world. You start noticing effort instead of service, livelihood instead of convenience, and community instead of scenery. As travelers, we have a responsibility to leave places better than we found them. Sometimes that means supporting local businesses, tipping fairly, remembering a name, or recommending a person instead of just a location.

Small things matter. Because when you know the faces behind the places, a destination stops being a backdrop. It becomes someone’s life. And once you see that, you don’t just visit anymore. You respect where you stand.

Hiring a Local Guide in Roatán– How To Contact Jorge

Jorge works independently, which means you’ll be speaking directly with the person who will actually meet you when you arrive. Because of that and because word of mouth keeps him busy, it’s best to reach out well before your trip to schedule time with him.

WhatsApp: +504 8975 1528

He offers:

- Airport transfers

- Ferry transfers (helpful if Roatán isn’t your final destination, like heading to Utila)

- Personalized island tours based on your interests and pace

When you message him, include your travel dates and what you’re hoping to experience. He plans his days carefully so he can give each group his full attention.

Planning Your Trip

If you’d rather not piece everything together yourself, you’re in the right place. I help travelers each year plan thoughtful, smooth trips to both Roatán and Utila — the kind where the logistics are handled so you can actually enjoy being there.

From timing the ferry connections to choosing the right area to stay and connecting you with the right local people, the goal is always the same: less stress, more experience.